Artículos

Social Representations and Acknowledgement of Human Rights in the city of Monterrey, México

Representaciones sociales y reconocimiento de los derechos humanos en la ciudad de Monterrey, Mexico

Social Representations and Acknowledgement of Human Rights in the city of Monterrey, México

Política, Globalidad y Ciudadanía, vol. 5, no. 9, 2019

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Received: 03 August 2018

Accepted: 02 September 2018

Abstract: This article focuses on the social representations of Human Rights in Mexican news media, in the city of Monterrey, Mexico. It analyses how Monterrey citizens learn about human rights, and what role could different sources play in their construction of social representations. Furthermore, it researches the acknowledgement and knowledge of the sub- ject by these citizens. The analysis is built on N239 surveys collected from Monterrey news readers, supplemented by data from twenty-four participants in four focus groups. The conclusions confirm that news media is the main source of information on Human Rights, but that there is a weak founded social representation regarding human rights. Attitudes are often fatalistic, and participants have limited knowledge of how to act upon human rights.

Keywords: Human Rights, Monterrey, news media, social representations.

Resumen: El artículo tuvo como objetivo indagar en las representaciones sociales sobre derechos humanos que hay en los medios mexicanos, particularmente en los de la ciudad de Monterrey. Analiza cómo los ciudadanos regiomontanos aprenden sobre los derechos humanos, así como qué papel juegan las diferentes fuentes de información en la construc- ción de sus representaciones sociales. Además, investiga el reconocimiento y conocimiento del tema que tienen dichos individuos. El estudio recogió 239 encuestas de lectores de noticias en Monterrey, y posteriormente se llevaron a cabo cuatro grupos de discusión con un total de 24 participantes. Las conclusiones confirman que los medios de comuni- cación son la principal fuente de información en materia de derechos humanos, pero los conocimientos son débiles. Además, las actitudes respecto a ellas son fatalistas, y los participantes desconocen la aplicación de dichos derechos.

Palabras clave: Derechos humanos, Monterrey, Noticias, Representaciones sociales.

1.- INTRODUTION

A simple online search of “human rights” and “Mexico” leads to an important amount of news articles, reports and other texts that discuss a list of human rights violations in the country. The organization Human Rights Watch, in its Annual Report of 2018 described a number of events in which Mexico failed to pro- tect Human Rights: forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, impunity and military abuse, tortures, prison system, attacks to journalists and human rights advocates, women and children’s rights, children migrants, sexual and gender identity, and people with disabilities (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

In December 10th, 2018, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights celebrated its 70th anniversary, since it was approved in 1948. Mexico voted in favor of this document along with other 47 countries, which means that, as a state, it would assume a commitment to look after the human rights of its citizens through all its institutions. This protection is part of International Law, which forces states to assume the obligations in order to respect, protect and promote human rights as well as intervene on its application. It is mandatory for states to adopt the necessary positive means to allow basic human rights to happen (PUDH UNAM, 2017). Several articles from the Mexican Constitution are either inspired or directly related to the articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, meaning, Mexico as a State has looked after a legal way to instate basic human rights. However, as mentioned before, the institutions haven’t been successful in guaranteeing all these rights to its citizens.

Even when human rights violations are a recurrent topic of journalists, and the Commission of Human Rights (both in state and national level) is a popular source of information for news, there seems to be a poor culture and knowledge in this respect. Often enough, there are confusing terms and facts regarding human rights, which lead to misinformation in the news’ audiences. This points to an early conclusion of how Mexico has failed in promoting the education of human rights in its population.

Human Rights is not a topic considered as a priority to learn at school (in contrast to the Mexican Cons- titution Law, rights and obligations of citizens, amongst other). It seems that the most likely source to learn about human rights, without specifically looking for them, is media, especially news. Based on this premi- se, this study aims to know what the main sources in the acknowledgement of human rights by Monterrey’s citizens are, and what do they know and understand by them in their context. The hypothesis is that news sources will be the most frequent and therefore most significant source of learning about human rights.

2.- LITERATURE REVIEW

The analysis human rights and public opinion has been explored from different disciplines, although ra- rely done with enough fieldwork to obtain representative results. Hertel, Scruggs & Heidkamp (2009) found in their research that Americans support human rights abroad, but their interest is fueled by global humani- tarian concerns and current events. In their surveys, they also found that their commitment to human rights weakens when it comes to the investment of national resources or to take risks on behalf of human rights.

According to Anderson, Regan and Ostergard (2002), the models of political action assume that people have information and act on it. By this reasoning, activists have been focusing an important amount of re- sources in making themselves visibles, especially through new technologies. “Today activists of all stripes recognize the necessity of having a presence online”, especially to attract younger generations (McLagan, 2002).

The other function on media related to human rights is to act as surveillance of the State, since it is through the exposure of abuses of public authority that the government is held to public scrutiny (Apodaca, 2007). In any way, whether it is to publicize a cause or to report State misconduct, this works as the distri-

bution of Human Rights information to its audiences.

This matters since, as McCorquodale & Fairbrother (1999) state, “when people know about human ri- ghts and are aware about human rights abuses, they are more likely to seek to protect them… and exposure can lead to changes in policy by the state concerned”. Therefore, the assumption would be that the more educated audiences are on human rights, the more they will care for them.

When learning about human rights and culture of legality is left only to news, then it becomes relevant to study the reception of this topic in news audiences. In order to delimit this reception study, we decided to choose seven news portals that are popular enough to be able to find participants that follow their publi- cations.

The analysis of this topic from a communication sciences perspective is remarkably unexplored, which justifies the relevance of this study. Two theories seem basic to understand the construction of their so- cial representations and their knowledge on human rights: Social Representations theory from Moscovici (2001), and Mediations theory from Martín-Barbero (1987) and Orozco (1997). Moscovici defines social representation as:

“a system of values, ideas and practices with a twofold function: first, to establish an order which will enable individuals to orientate themselves in their material and social world and to master it; and secondly to enable communication to take place among the members of a community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and classifying unambiguously the various aspects of their world and their individuals and group history” (1976, p.xiii).

The reason why it is important to learn about individual’s social representations on human rights is because it is a cognitive system that includes stereotypes, opinions, beliefs, values and norms that lead to attitudes and behavior of people. Social representations work as guidelines for a community of people, sin- ce they become the collective consciousness on certain topics, allowing that community to act accordingly in a way that becomes acceptable to all members (Araya, 2002).

It is important to reflect on the fact that knowledge is an important element of social representations. Based on what people know, whether it is correct or incorrect, they will construct their attitudes and beliefs around that topic. If Monterrey citizens have a low knowledge regarding human rights, then there is also a possibility that the social representations constructed around them are based on intuition or weak founda- tions.

The question that follows would be: how Monterrey citizens learn about human rights, and what role could different sources play in their construction of social representations. For that matter, we will revisit Mediations theory which was originally proposed by Martín Barbero (1987). Both theories consider mass media as a significant source of information in the formation of attitudes, beliefs and so on of individuals.

Orozco (1997) was the first to operationalize Martin Barbero’s Mediation theory into four categories: individuals (which are subdivided into cognitive and structural), institutional (family, religion, state, me- dia…), video-technology, and situational. This paper is focused in the individual (which will take into con- sideration their knowledge, comprehension, interpretation and attitudes on human rights) and institutional (which will look at news portals or other media sources that participants consume with certain frequency).

The results of this project will sustain that knowledge of human rights is basic when it comes to the defense and promotion of a society that has a healthy justice and social system. The more aware individuals become of the universal human rights, the better they can become advocates in their societies and influence

state power to keep their protection.

The following section will explain the methodology designed to obtain the participant’s knowledge, attitudes and opinions regarding human rights.

3.- METODOLOGY

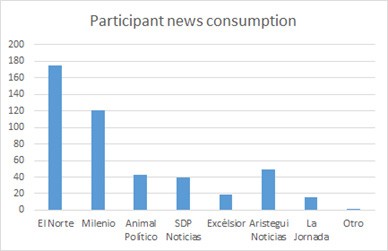

In order to study how Monterrey news followers understand human rights, we collected 239 surveys with adult inhabitants of the city and organized four focus groups, who read at least one of the following news portals: El Norte, Milenio, Animal Político, SDP Noticias, Excelsior, Aristegui Noticias, or La Jor- nada. This criterion was a filter question to select the participants of the survey. If the person didn’t read or follow any of the news portals listed before, then the survey would not be responded by him or her.

The approach of this project was explorative, and did not intend to be representative of the population analyzed. Due to the lack of information and studies done in this topic, it was rather necessary to do a qualitative examination that responded to the question of how much do Monterrey’s adult news readers perceive they know about human rights, and what role do they give to news in that knowledge. This was done through mixed methods: survey and focus groups.

The population of Monterrey is considered to be ideologically right wing due to the industrial and com- pany history behind it. It’s one of the three largest cities in Mexico, and the closest one to the border of US, which is noticeable in its influence. Considering that the most important news portal due to its popularity is El Norte, we can also deduce that the population has a tendency towards conservative politics. For the purpose of diversification, we chose an ideological variety of news portals. A brief description of all the news portals mentioned earlier:

El Norte. This is the local version in Monterrey that belongs to Grupo Reforma. It has the largest amount of printing and is traditionally conservative and right wing (which represents the local culture).

Milenio. Slightly less conservative than El Norte, is the second most popular newspaper in Monterrey.

It belongs to a media conglomerate called Multimedios.

Animal Político. It is an independent news portal with no printed version. It is well known for their research journalism focused on corruption scandals, and also for pointing out human rights violations.

SDP Noticias. It’s also only available in the digital version, although they barely have any information of their editorial board and sources. It is particularly popular in social media thanks to their spectacularized titles.

Excelsior. It is one of the most important national newspapers, and a news portal that has free access.

Ideologically, it can be considered to have a tendency to officialist.

Aristegui Noticias. It is a fully online news portal. Carmen Aristegui became popular through her radio show, and after she investigated a corruption scandal of the First Lady and the President Enrique Peña Nie- to, she got fired. She became an independent journalist who still keeps a significant number of followers, and ideologically is well known as progressive.

La Jornada. This newspaper is known amongst the most left wing, since it usually covers stories regar- ding labor rights, corruption scandals, social inequality problems, etc. It has a national reach.

The survey was applied by a convenience sample, in different spots from the city as well as through

snowball technique. The questionnaire was composed of 28 both open-ended and multiple options ques- tions. It explored how much the respondent knew about human rights; what social groups they believe deserves more attention by the human rights commission; what are the main needs in Mexico and for them- selves; how do they interpret certain articles from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and what news portals are they used to visit as well as which ones focus on the topic of human rights.

Regarding the profile of the participants, 68% were women, ages 17-75. The majority of the participants were in their twenties. 54.4% had a university diploma or were currently university students2. 50.2% follow news through their Twitter account, 70.3% through their Facebook account, 43.5% visit the news websites by their own initiative, 21.3% buy printed newspapers, and 13.8% have an APP of a news portal to follow news.

After an analysis through IBM SPSS Statistics, we designed a guide to explore deeper into certain ques- tions with discussion groups. Each of the four discussion groups had six participants with a profile similar to the survey respondents, which means that we had a total of 24 individuals for the qualitative stage of this project. Afterwards, these focus groups were transcribed and later analyzed.

During the focus groups, we analyzed different categories in order to explore further the comprehension that the participants had on human rights. The different categories were: learning sources of human rights, reception of news on human rights, labor related human rights, interpretation of certain articles, and per- ception of human rights in Mexico.

The profile of the participants were adults ages 20-30. Half of them had a full-time job, and the other half were university students. The purpose of these two profiles was mainly to compare the perceptions on the category of labor human rights (human rights that would interest anyone who is employed, such as social security, retirement, minimum standard of living, paid vacations. ). For the rest of the categories, we

found no significant differences.

A special thanks is entitled to students of Theories and Research Methodologies group, of the program for Communication and Information Sciences of Universidad de Monterrey. This specific generation took the course in the months August-November 2017.

4.- RESULTS

The results section is divided in three parts: 1) Participants and news consumption, which offers a gene- ral description of the participants viewpoint on human rights and consumption of news, given that the main filter was based on what news portals they visit more frequently; 2) Participants understanding of human rights, which will point out the comprehension that they have on the topic, as well as what participants feel most confused about; and 3) Participants and their perception of human rights in Mexico, because most of the attitudes are based not on the need of human rights globally, but on the pursuit of them in Mexico.

Participants and News Consumption

The main criterion for choosing the participants was whether they followed news portals.

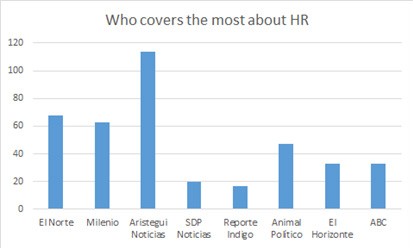

The consumption is in line with the popularity of the local newspapers, meaning, the most printed pa- pers are also the ones that are consumed the most by our participants. Their perception on who speaks the most about human rights, however, changes from what they consume the most:

The majority of the participants identify Carmen Aristegui’s news portal as the most preoccupied with the topic of human rights violations, which is in line with her reputation of pointing out the scandals related to government and politics. It seems like the participants are not particularly interested in following news that cover human rights stories, since they correctly pinpoint what news portals discuss it the most, howe- ver, they don’t actively follow or read these portals. The following graphic shows where participants learn about human rights from:

This shows a tendency on how participants do not have initiative to follow human rights news, since most of them learn about the related stories through their social media. While most of what they read co- mes from the Facebook or Twitter account of news portals, this depends entirely on what appears on their newsfeed since they don’t actively look into news websites or newspapers to learn more about it. This is problematic when we consider the factor of social media algorithms, after all it is not guaranteed that even when you follow certain news portals you see all posts from that page.

The focus groups were consistent with this result. While there were participants that remember learning about them at school or at specialized courses, the majority hear and learn the most of human rights through news (in all of their formats). Rarely they buy a newspaper or watch TV news, but they follow news portals and therefore they read about them in their Facebook and Twitter accounts.

During the conversations in the qualitative sessions, they mostly indicated that they associate human rights with bad news, considering they have never heard of a successful case globally. They believe that while they are needed in different circumstances, the UN and the National Commissions of Human Rights don’t seem to have much power other than writing recommendations to the government (Alejandro, session 3). All of the participants believe that in the Mexican case, the government doesn’t care about citizen’s human rights.

In other regards, 33.9% of the participants (81 individuals) say they have read the full list of Human Rights (from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights). This means that a third of the respondents would have a minimum base of knowledge of what are the human rights in the first place.

When discussing what cases on human rights they remember the most, we asked separately for Mexico and for the world. For Mexico, they mentioned the most popular crime news even when they mentioned some that were not directly related to human rights. The most frequent responses were the Ayotzinapa case (43 missing students in a rally), the murder of Mara Castilla (rape and murder by a Cabify driver), earthquake corruption scandals (Oaxaca, Chiapas and Mexico City disaster and with corrupt construction contracts), central American migrants (rape, murder, kidnapping, torture…), indigenous communities (dis- crimination and aggression), journalists (murder, kidnapping, threats), feminicides, and other gender crimes (such as LGBTQ+ discrimination, controversy of same sex marriages).

On global cases they mix sources from news and documentaries. They mentioned the shooting in Las Vegas (October 1, 2017), Venezuela (with no further explanation), KKK in US, DACA retreat in US by Trump, Black Lives Matter’s causes, shooting in club in Orlando (June 12, 2016), Catalonia’s rallies, Ban- gladesh’s factory collapse and labor conditions, War in Syria, countries where homosexuality is considered illegal, women’s rights in different countries, and migrants in different regions (Africa, Asia, Latin Ameri- ca).

It is important to point out that both of these questions were open ended, therefore, participants would mention whatever came to their minds in this regard. As it is evident in the cases, not all of them are human rights violations (implying systematic failure of the state), but other types of crimes. This already suggests that there is confusion on the topic amongst the respondents.

The multiple choice question we asked was: “Which are the most popular human rights mentioned in the news?”, for which they chose Liberty of opinion and expression (Freq: 87), Right to life, liberty and security (Freq: 46), and Right to education (Freq: 38). For the first, it is related to the insecurity that jour- nalists face nowadays in Mexico, since it is one of the countries where this career is considered one of the most unsafe. The second, consistent with the insecurity for journalists, is the violence wave in Mexico in the context of drug war and corruption, for which impunity is clear and constantly pointed out in the news. Regarding the right to education, it appears in news related to corruption scandals within the schools or the syndicate of teachers. Less frequently, this is connected to violence in schools.

Participants and their understanding of Human Rights

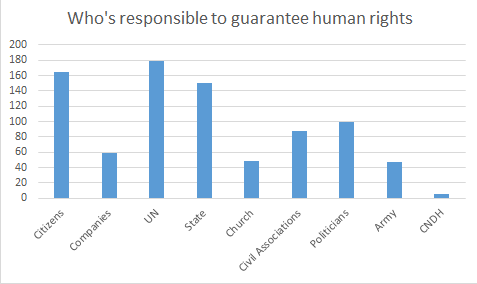

We start with the question of responsibility. Given Human Rights are public international law, they are primarily rules regarding the conduct of states, in this case the obligation of the state to protect, provide and respect certain rights regarding human dignity. Our research indicates that there is confusion about what institution or figure is responsible to guarantee the citizen’s human rights in Mexico, as we can see in Graphic 4:

For this question, participants were able to choose as much responses as they wanted. In the most fre- quent replies, they marked UN and citizens as the ones who are the most responsible to guarantee human

rights, and State comes only until the third option with 150 responses. Based on the discussions in focus groups, we were able to understand that the majority didn’t precisely understand that the violations of hu- man rights come from public authorities (or their failure to protect against them), confusing it with other type of crimes.

We left an “other” as an open-end question and that’s when CNDH was mentioned five times. However, during the focus groups, even the most knowledgeable participants didn’t know there was a State Commis- sion of Human Rights (CEDH). When we asked where to file a complaint regarding human rights, nobody knew that the commission was the place to go. They would mention other figures such as the police, the army, or private lawyers. However, in most scenarios, they mentioned they wouldn’t dare to file a complaint in Mexico out of fear. In this regard, they pointed out the government as the figure that most violates human rights; in less frequency, they mentioned police and military, and one participant mentioned “the biggest companies”.

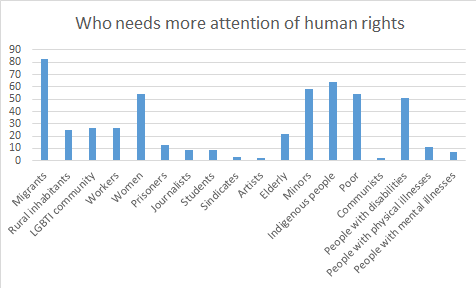

Regarding what social groups deserve or need the most attention from human rights commission, parti- cipants could choose two options from the following (plus an open “other” who had almost no responses).

According to this graphic, migrants (Freq: 83), indigenous people (Freq: 64), minors (Freq: 58), women and the poor (both freq: 54) are the most in need. In the open end responses some indicated that “everyone” is in need, while one replied “colored people”. However, this differed from the discussions in the qualitative sessions, since when we asked if the participants belonged to a group that had need for human rights, most of them replied they didn’t. Meaning, they don’t consider themselves vulnerable in this matter (even when there were women participants).

They actually pointed out that the need for human rights protection is strongly related to social class. They mentioned how often they see that the poor are the social group that gets the most violated in their rights, since they unjustly convict them, accuse them, fail to protect them and so on. They recognized this doesn’t happen with upper classes, since even when they’re guilty of charges, they get an acceptable or good treatment by law. The conclusion after this discussion was that corruption plays an important role in how human rights are respected to each individual.

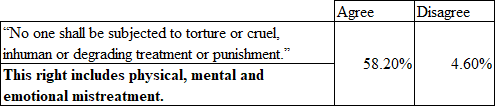

In a specific section of the survey, we transcribed two articles: the 5th and the 16th. The exercise con- sisted in identifying their interpretation of these articles on a writing gap or misinformation due to the lack of specification in the human right as it is in the Declaration.

Many participants of the survey seemed confused about this article, since a significant amount decided not to reply due to a lack of information. In any case, it seems like the majority believes that torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment is not only about physical aggression, but also psychologi- cal. Article 16 is more related to gender rights for the LGBTQ+ community:

Mexico, and specially cities like Monterrey, have a typically conservative society, and has been discus- sing throughout the last years the LGBTQ+ rights. While in the Constitution gay marriage is legal, States are autonomous in deciding whether this is acceptable within the states or not, which is not the case for Nuevo Leon that doesn’t allow gay marriage up to the moment when the survey was done (state where Monterrey is located). The majority of the states do not marry gay couples at the moment.

Based on this response, the participants have already a very clear position regarding gay marriage, but they don’t when it comes to adoption in homoparental families. In any case, the majority of the respondents agree that the way this human right article is edited, leaves a space of interpretation to allow gay marriages and adoption to be part of that right.

Considering how these three questions worked in the survey, we decided to include this exercise in the focus groups with other articles. We first added article 3: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person”, and asked since what moment this right is applicable: conception, since the birth, or when would they mark the starting point. Most of the participants were confused and looked like they didn’t have a clear position. However, the majority considered that conception was the starting point, since they were against abortion. Only three participants indicated that since birth, and one mentioned from four weeks since conception. Based on this, the term “everyone” would include embryos and fetuses.

Another article that was discussed was the 23rd: “(1) Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment. (2) Ever- yone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work. (3) Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection. (4) Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests”. The question we asked was “How does this right work with people with informal unemployment, such as domestic employees, construction workers, outsourcing, etc.?”

In Mexico, 57.2% of the occupied population has an informal employment (Cruz, May 17, 2017). This means that these employees do not get the mandatory benefits such as social security, savings funds, retirement funds, paid vacations, etc. This became an uncomfortable question since the majority of the participants admitted they have domestic employees without a contract. However, some believed that they gave the legal benefits to their employees by feeding them or giving them a room in case they were “stay-in maids”. Only one participant pointed out a State initiative to promote formal contracts for domestic emplo- yees. But no clear answer was given by anyone on how this human right applies in the Mexican scenario.

In general, we noticed a lack of comprehension of human rights. When we asked if they thought new human rights should be included now in the declaration, they mostly indicated that probably there is no need to add, but there is definitely a need to be clearer and more specific about the articles that already exist.

Participants and their perception of Human Rights in Mexico

90.8% believe that when a State doesn’t guarantee human rights to their population, an international intervention should be done. It is interesting to see that 95.8% of the participants think that Mexico has a problem in respect to the violations of human rights. Based on these responses, participants would agree with an international intervention in Mexico.

This is coherent with what has been explained before since the majority of the participants, both in surveys and discussion groups, have a deep mistrust in Mexican authorities. Based on an INE survey, only little over 20% of the Mexican population trusts the police force in Mexico, less than 30% trusts the muni- cipal or state government, and close to 35% trust the federal government (Hernández, 2014). We must keep in mind this refers to the Peña Nieto era. This is consistent with the attitudes of the respondents.

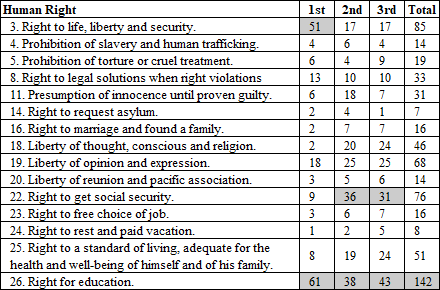

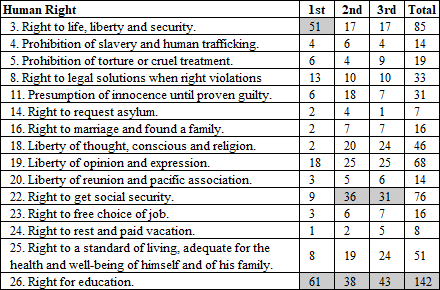

The following tables had the objective to identify which human rights do the participants of the survey believe are the most important for them, for Mexico and for the world. For this exercise, we shortened the list and worked with the rights that appear in the following tables, with the purpose of using the most po- pular ones mentioned in the pilot survey we initially did. When it comes to what human rights they believe are the most important for them, we asked them to choose three in order of importance:

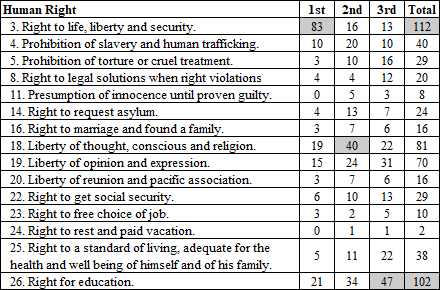

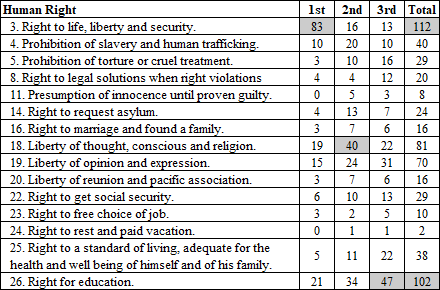

When it comes to the needs of Mexico, the result changes to more basic types of services such as se- curity, social security and education. While Mexico has institutions that look after free access to school, health care and police force, constantly is seen in the news that there are corruption scandals in all public secretaries and political figures which means there is a failed effort from the State in accomplishing this human right. Therefore, it is not surprising to see that this is what most participants identify as urgent for the majority of the population. And finally, on a global scale this is what they pointed out:

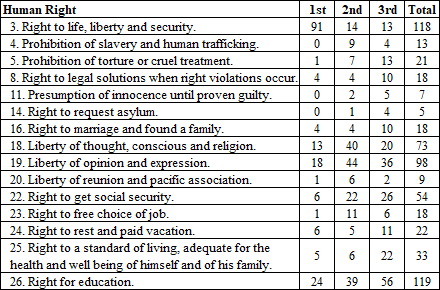

On a larger scale, education, life, liberty and security are repeated. This reflects the values of the par- ticipants since it is something that is consistent also in the individual level. In respect to life, liberty and security, it is consistent as well with the human rights cases they remember since they are mostly related to insecurity and violence. While none of the participants indicated that they ever needed to file a complaint by being victims of a violation of human rights themselves, they still feel aware of the insecure context around the world.

As mentioned before, most of the participants showed mistrust to the government and public authori- ties. However, they pointed out that insecurity was not an issue that only Mexico had, since they compared organized crime in this country with terrorism in other regions like Europe. The most influential mediation is easily identifiable as mass media, since all of the mentioned sources for these cases were social media, news and documentaries.

Compared to what survey participants believed are the most popular human rights in the news, all three come up as what they consider the most important ones for themselves, Mexico and the world. Adding up to them, they also indicated Liberty of thought, conscious and religion and Right to social security. 31 participants believe that the Right to social security comes up often in news, and 27 believe that Liberty of thought, conscious and religion is frequently in the agenda, which are lower figures than the other three.

When we asked out of this list which human rights participants believed were going to be included in the agenda of the presidential candidates in 2018, there was barely any agreement, but the most mentioned

ones were Right to life, liberty and security; Right for education; and Right to get social security. Again, all of them are within the human rights that are perceived to be the most popular within the news agenda.

5.- CONCLUSIONS

Three main conclusions can be drawn to understand the acknowledgement of human rights amongst Monterrey citizens. The first one is regarding the misinformation and lack of interest in the topic of human rights; secondly, identifying the role of news and other sources in their acknowledgement of human rights; and third, the pessimistic attitude of the impunity and corruption in Mexico.

Unfortunately, as expected, there is a weak founded social representation regarding human rights. Most of the participants in surveys and focus groups base their knowledge (and therefore their attitudes, inter- pretation, beliefs and so on) in information that arrives to them without them looking into it. Indeed, most of what is seen in the news (which can be considered the main source of learning about human rights) is pessimistic and even at some point fatalistic, which can explain their deep mistrust and negative viewpoint on the topic. In this regard, there is a need to do some educational efforts in order for people to first know their human rights, and second, how to act upon them.

Considering that mass media is probably the most important way to establish and strengthen social representations (since it represents in a consolidated form all topics and standpoints of a society), then the Commission of Human Rights should consider campaigns to both educate journalists and promote their role in society. On the one hand, the role of journalists should be that of an expert in the topics they’re writing or reporting about. If the journalist him/herself doesn’t know about human rights and their correct terms, then most probably misinformation will be broadcasted. On the other, the Commission of Human Rights and the State have as a clear responsibility the promotion of human rights. If they don’t do more efforts on getting known by the population, they definitely have failed in one of their objectives.

Second, the hypothesis on news playing a significant role on people’s learning of human rights was confirmed. While the news arrives to audiences through different platforms, the format is the same: people read about human rights when it comes to news-reporting and cases of violations, typically unresolved. This adds up a responsibility to journalists as explained in the first conclusion from the past paragraphs.

And third, the fatalistic viewpoint has probably created resistance from the part of the population on wanting to learn more about it, since they all agreed that human rights news is always “bad news”. The perception of the participants is that there is nothing they can do because violations are mostly done with corruption, and as stated in the article, there is a clear mistrust in authorities. In a very comfortable position, the majority of the participants expect an international-external institution to intervene Mexico in order to resolve this problem of corruption and impunity. Another value that could be promoted by journalists should be citizen empowerment. That way, by learning what can be done, what are the human rights, where to report violations; there could be individuals that get interested in also contributing to the solution of problems and the promoting of human rights.

In this matter, we could see how institutional mediations are the most influential in learning about hu- man rights. However, due to lack of interest and/or understanding, it doesn’t transcend in a significant way into individual’s attitudes, thoughts, emotions or general knowledge. Based on this, we can affirm that there is a weak or practically nule social representation of human rights in general in Monterrey’s news readers.

In the meanwhile, learning about a population’s social representations on human rights can shed light on how much culture is enabling the failure in the protection of human rights in a country like Mexico. Finding out what sources are also contributing in the construction of these social representations, should inspire the

involved institutions and authorities to do a better job in communicating knowledge and a better attitude towards human rights protection.

There is evidently need for more studies in this matter. Future research should focus in comparing in- dividuals who are not active news readers with those who are, to see if there is an actual difference in their fatalistic point of views; as well as more studies in different regions to find out if there is difference in their understanding and knowledge of the topic.

References

Anderson, C.; Regan, P. & Ostergard, R. (2002) Political Repression and Public Perceptions of Human Rights. Political Research Quarterly 55 (2). Pp. 439-456. DOI: 10.2307/3088060

Apodaca, C. (2007) The Whole World Could Be Watching: Human Rights and the Media. Journal of Human Rights. 6. Pp. 147-164. DOI: 10.1080/14754830701334632

Araya, S. (2002). Las representaciones sociales: Ejes teóricos para su discusión. Costa Rica: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) y Agencia Sueca para el Desarrollo Internacional (ASDI).

Cruz, J.C. (May 17, 2017). Con empleo informal, casi 6 de cada 10 mexicanos: INEGI. Proceso. Retrieved from: https://www.proceso.com.mx/486719/empleo-informal-casi-seis-10-mexicanos-inegi

Hernández, A. (June 17, 2014). 42% de los mexicanos no confía en sus autoridades, revela el INE. El Financiero. Retrieved from: http://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/politica/42-de-los-mexicanos-no-confia- en-sus-autoridades-revela-el-ine

Hertel, S.; Scruggs, L.; & Heidkamp, P. (2009) Human Rights and Public Opinion: From Attitudes to Action. Political Science Quarterly 124 (3). Pp. 443-459.

Human Rights Watch (2018). México. Eventos del 2017. In Informe Anual 2018 - Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/es/world-report/2018/country-chapters/313310

Martín-Barbero, J. (1987). De los medios a las mediaciones. Comunicación, cultura y hegemonía. Colombia: Convenio Andrés Bello.

McCorquodale, R. & Fairbrother, R. (1999) Globalization and Human Rights. Human Rights Quarterly 21(3). Pp. 723-766.

McFarland, S. & Mathews, M. (2005) Who Cares About Human Rights? Political Psychology 26 (3). Pp.

McLagan, M. (2003) Principles, Publicity, and Politics: Notes on Human Rights Media. Visual Anthropology. 105 (3) P. 605-612.

Moscovici, S. (2001). Social representations. Explorations in Social Psychology. New York: New York University Press.

Moscovici, S. (1976). Social influence and social change. Academic Press.

PUDH-UNAM (2017). Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos. Programa Universitario de Derechos Humanos de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Retrieved from: http://www. pudh.unam.mx/ONU_declaracion-DH.html

Orozco, G. (1997). Medios, audiencias y mediaciones. Comunicar (8). Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc. org/pdf/158/15800806.pdf